Mentioning The War, Pt. 79

Let's check in on that Summer Offensive and get a little more realistic nuance added to our picture. Слава Україні!

So, you may have noticed that things are going slowly in Ukraine’s much-vaunted summer counter-offensive. It’s true! They have thus far not been able to obtain the kind of sweeping breakthrough that sends Russian occupiers scrambling back to the 1991 borders ahead of a hard-charging line of western-surplus tanks and AFVs and the mechanized divisions into honored immortality.

Does this mean Ukraine is losing? Does it mean that this offensive has failed? No and no. It means expectations were too high and the general western media understanding of combat operations is limited to a couple of extremely asymmetric wars run by the US (and partners) against completely overmatched opponents.

What Ukraine is attempting here is a combined-arms offensive aimed at penetrating layered belts of prepared defensives with literally millions of mines used to funnel their advances into previously-prepared artillery kill boxes. This is World War One, the remix. Combined arms into prepared defenses is never easy, especially if you haven’t got much experience—as Ukraine hasn’t. It took the world’s leading military powers years and years of bloody warfare to figure it out a century ago, and they haven’t done it since without one key force aspect that Ukraine doesn’t have: air superiority. Ukraine lacks either air superiority or air dominance. The US-led coalitions that fought Iraq—a decidedly easier target than the Russian defensive works here—spent the first forty days of that conflict conducting a series of airstrikes to first achieve air superiority and then pound logistics from above with impunity. Then, when the attack began, air superiority meant that the US maintained a monopoly on rapid reaction: no surprise anti-tank sorties, no surprise artillery, and any enemy position that put up a fight could be isolated and pounded from above, sparing your assault troops the hardest work.

This is blowtorch and corkscrew stuff.

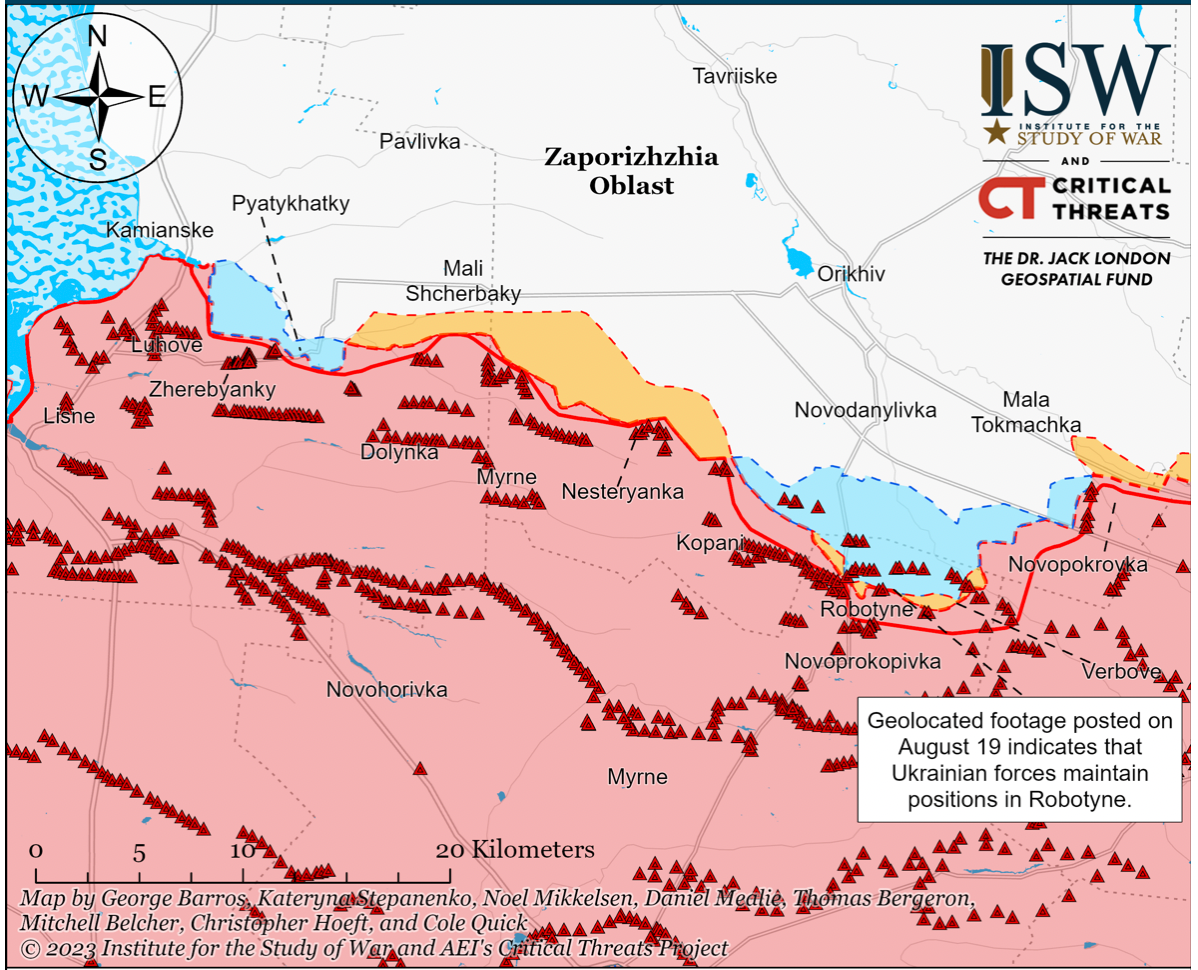

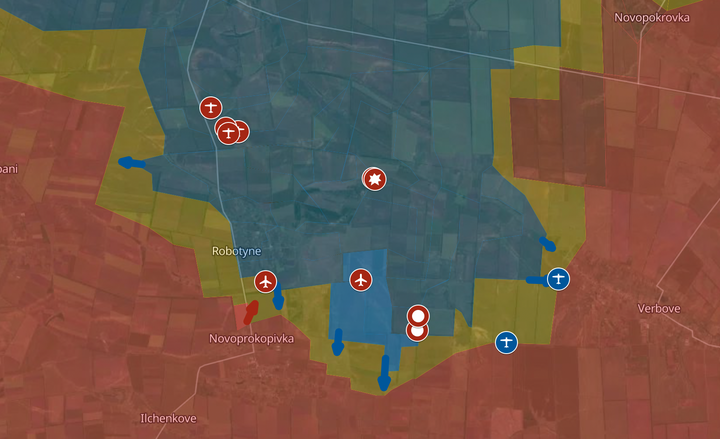

Ukraine doesn’t have this. They don’t even have a suitably large complement of engineering and breaching equipment. They are doing WW1 combat the hard way. This is blowtorch and corkscrew stuff. They learned quickly that Russia’s army was fully prepared to defend the trench lines and shifted tactics. Their counter battery fire has become truly excellent and has systematically reduced Russia’s defensive artillery emplacements. Their use of their limited stocks of cruise missiles has focused on logistical hubs and bridges, to reduce resupply. They’ve started to try to draw Russia’s dwindling stock of attack helicopters—the cavalry of modern warfare—into vulnerable zones and are using short-range air defenses to knock them out. They requested and received cluster munitions—perfect for their design goal of suppressing entrenched infantry.

In short—they stopped looking for a breakthrough after the first shock and spent a long while instead trying to create the conditions in which they might produce one via asymmetric attritional use of precision fires. Russia has lacked for such precision, especially in a counter-battery mode; they’re losing artillery and helicopters much faster than they can replace them. The offensive appears, to my eye, to be setting the conditions for winning the war. It may not get there this year. Ukraine and her partners need to be preparing a 2024 effort now.

But what are we to make of the Russian army holistically? We’ve constantly heard and seen evidence that it is low-morale and beset by myriad problems. This is all probably true. I have maintained since last summer that it isn’t an army you can win an offensive war with, but it is an army you can play solid defense with. These World War One style trenches are easy for even low-quality, poorly supplied troops to defend. Minefields don’t get low on morale. The arms of the Russian military that do work well: their artillery corps and air force, get to play an outsized role in blunting the most serious breakthrough efforts. Thanks to their vast stocks of materiel—though contracts with Iran and North Korea indicate they’re running low—they have had supplies enough to cover logistical setbacks through sheer volume.

Russia has also elected to defend in a very reactive way—we’ve seen huge numbers of their rested reserves committed up and down the line trying to dislodge and counter any Ukrainian advance, often with horrific consequences for their forces. This is puzzling—the point of trench works is defense in depth, but the aggressiveness of the counter-counter would seem to imply they’re thinking of this more as a shallow crust of defenses. More information is needed here.

Nobody's ever won money predicting Russia's military collapse...

It's tempting—and we've seen a lot of folks try—to predict that Russia's on their last legs. Nobody's ever won money predicting that “this time, surely the Russian army has taken enough punishment and will collapse” throughout history. Many have relied on such forecasts to their ultimate downfall. Ukraine and her partners would be wise to proceed as if Russia can keep this up for years to come, even as they strive hard to ensure they can’t. Don’t forecast when your adversary will crack—work to create favorable conditions for the breakdown and try like hell to exploit it when it happens. Optionality runs everything around the battlefield.

In the last few days, we’ve seen Ukraine go back over to maneuver in this more slightly more favorable combat space; early results are intriguing—they are in the defensive belt-works now, fighting hard. They appear to be doing what I would like to call “squeezing the egg.” They’re attacking—asking questions—at numerous locations along the entire front. The thing about playing defense as Russia is doing here is that they need to come up with a good answer for every question. Ukraine just needs one wrong answer from them. If they can start cracking that egg somewhere where they have fresh mechanized reserves, they might yet produce that sought-for sweeping breakthrough this fall.

Even if they don’t, the summer of attrition coupled with increased access—one hopes and prays—to more long-range fires and, “oh come on please western partners” F16s—less for the airframes and more for their payload’s ability to challenge Russian air supremacy and maybe build towards some local air dominance for the winter and spring.

Meanwhile, NATO countries have got to ramp up production of ammunition and replacement parts. The quicker Ukraine’s artillery gains and extends a logistical edge, the quicker the war ends. NATO can either facilitate Ukrainian victory “on the cheap” (for NATO, the price is brutally high for Ukraine already), with spare machines we were going to scrap or mothball anyway and ammo, or they can freeze the conflict and face another costly cold war which would embolden all of the west’s geo-strategic rivals.

Слава Україні!

Comments ()