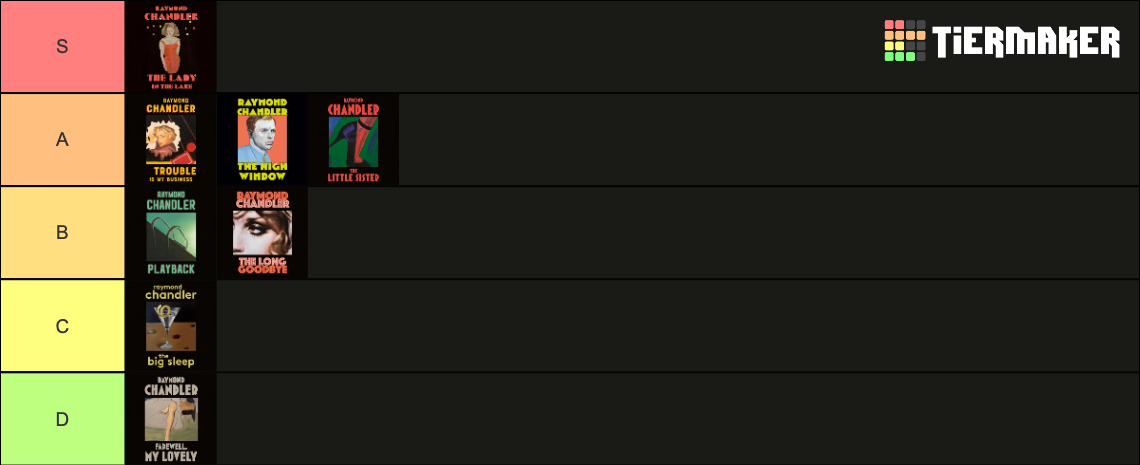

The Raymond Chandler Tier List

I recently "batted the cycle", re-listening to all of the Philip Marlowe stories—so what better time to but them in a tier list?

“Trouble is my business,” I said. “How else would I make a nickel?”

Ah, Phil Marlowe—the wryly observant student of human character... quintessential tough guy, romantic at heart, master of the witty retort. You can see the tier list above, but I thought I'd offer a couple quick thoughts justifying myself... and a memorable quote from each selection, to keep things interesting.

Also, a quick note on reading Chandler in this day and age: I think a lot of the problems and themes from these most traditional of noir stories remain relevant today, and in looking at how Chandler writes Marlowe and the other white men around him, we can see several paradigms of toxic white masculinity unfold very cleanly and clearly before us. I think it's important to acknowledge that. There's both something to learn from the text and from the meta-text.

- Trouble is my Business is a collection of four short stories—the eponymous "Trouble is my Business", "Finger Man", "Goldfish", and "Red Wind", plus an introductory essay on the subject of pulp fiction in general that is absolutely not to be missed. All of the stories are solid, but "Red Wind" deserves special mention for the subtly sentimental way Philip Marlowe handles the case resolution—a glimpse of a softer, gentler future that seems forever just out of Marlowe's reach. Solid A.

"I need a man good-looking enough to pick up a dame with a sense of class, but tough enough to swap punches with a power shovel. I need a guy who can act like a bar lizard but back-chat like Fred Allen, only better..."

"It's a cinch," I said. "You need the New York Yankees, Robert Donat, and the Yacht Club Boys."

- The Big Sleep is perhaps most memorable for introducing Hollywood—and everyone else—to the pairing of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, but it is also a pretty decent first outing for Marlowe: sleaze, gamblers, racketeers, and a well-worked twist. If you've recently read Trouble is my Business, then you'll recognize sections of the book that are cribbed and remixed from a couple of the short stories. The book is marred by homophobia and casual mild racism, though so as much as I like the plotting here... I can't rate it higher than a C—the movie avoids those pitfalls, at least, but is less intricate.

"I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn't care who knew it."

- Farewell, My Lovely is my least favorite novel—although it has some excellent scenes with what we'd call a new-age guru, an offshore gambling yacht, a ring of jewel thieves, and a giant of a man on a mission to find his long-lost love—it has far, far too much casual racism (including Marlowe casually dropping the n-word) to be a comfortable experience. Fortunately, things get a lot better on this from from here. Would be a B, instead: D.

“I needed a drink, I needed a lot of life insurance, I needed a vacation, I needed a home in the country. What I had was a coat, a hat and a gun. I put them on and went out of the room.”

- The High Window re-introduces us to Marlowe the romantic-at-heart in a very touching way, as he unspools the trauma connecting a wealthy widow, her secretary, her failson, a blackmailer, a missing wife, and a stolen rare coin. A solid A. It also really brings forward Marlowe's "ACAB" leanings—Chandler's extreme skepticism that authorities can be trusted boils over at several points, viz:

“Until you guys [the police] own your own souls you don't own mine. Until you guys can be trusted every time and always, in all times and conditions, to seek the truth out and find it and let the chips fall where they may—until that time comes, I have the right to listen to my conscience, and protect my client the best way I can.”

And it has one of my all-time favorite closing lines, which never fails to get me a little misty-eyed:

“I had a funny feeling as I saw the house disappear, as though I had written a poem and it was very good and I had lost it and would never remember it again.”

- Now The Lady in the Lake is a pitch-perfect noir. The plot unfolds in 1942, but the all-consuming World War is kept at an almost surreal remove, providing a backdrop for this story of Marlowe investigating not one but two missing wives. One rich, one poor, neither quite what or who they seem, and the whole story is resonant with enchanting imagery that conjures a more symbolic-feeling, almost Arthurian quest. It is also the greatest display of Marlowe's deductive reasoning skills. It's great to spend time outside of L.A., and it lets us see that noir can leak out of the big city. An easy S.

“Everything was quiet and sunny and calm. No cause for excitement whatever. It's only Marlowe, finding another body. He does it rather well by now. Murder-a-day Marlowe, they call him...”

- In The Little Sister, Marlowe goes to Hollywood to root around in the seedy underbelly of that glitzy and glamorous industry... and Chandler gets to unload the full force of his disenchantment with the movie business. The story opens quietly, with Marlowe trying to find the titular little sister's brother, who has naturally gone missing. This, of course, escalates into a little blackmail, a lot of drugs, and more than enough murder for poor "Murder-a-day Marlowe." I don't like the somewhat famous "you're not human tonight, Marlowe" rant—it strikes me as so much ranting from Chandler—but I really like the denouement. Clings to an A.

“I hung up. It was a good start, but it didn’t go far enough. I ought to have locked the door and hidden under the desk.”

- Chandler's most melancholy novel, The Long Goodbye, features not just one but two loose authorial surrogates in pivotal roles, trying to explain themselves and their life choices to a very weary Phil Marlowe. This is a slow burn character study rather than pulp, and lots of people really like it. As for me, it always seems like a bit much—Chandler, like Marlowe, is fed up with the "lifestyles of the rich and famous"—and while I think it drags a bit much, the high quality of prose throughout means it clings to a B. This ode to a friendship borne of happenstance and longing is Chandler's trap novel.

“There is no trap so deadly as the trap you set for yourself.”

- And so we come to Playback, the shortest of the novels, one that feels like a farewell to Marlowe—I know Chandler was working on another before his death (Poodle Springs, later completed by Robert Parker)—and this one is many people's least favorite. I like it, though it is more straightforward, shorter than the others, and sees Marlowe admit he's getting older, more abrasive, and lonelier. As a swan song, this is so close to an A... but the plot is stretched out like too little butter over... wait, that's the wrong series :). Don't listen to anyone who'd tell you to skip Playback—just go in knowing it is a "short goodbye" and that you'll be melancholically happy for a phone call Marlowe gets towards the end, offering our world-weary questing knight a lifeline.

“I'm not a young man. I'm old, tired and full of no coffee.”

and

“Wherever I went, whatever I did, this was what I would come back to. A blank wall in a meaningless room in a meaningless house.”

Anyhow, I keep coming back to these stories for the excellence of their eye, the sharpness of the dialogue, their outright and unexpected bits of comedy, and the enduring realism of their characters and themes. And for their unflinching portrait of past societal problems that aren't even past...

Comments ()